- Home

- Thomas Hodd

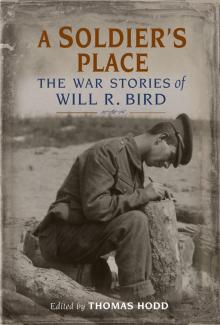

A Soldier's Place

A Soldier's Place Read online

Introduction copyright © Thomas Hodd

Stories copyright © Estate of Will R. Bird

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior written permission from the publisher, or, in the case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, permission from Access Copyright, 1 Yonge Street, Suite 1900, Toronto, Ontario M5E 1E5.

Nimbus Publishing Limited

PO Box 9166

Halifax, NS B3K 5M8

(902) 455-4286

nimbus.ca

Interior and cover design: Heather Bryan

NB1352

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Bird, Will R. (Will Richard), 1891-1984

[Short stories. Selections]

A soldier’s place : the war stories of Will R. Bird / edited by Thomas Hodd.

Includes index.

Issued in print and electronic formats.

ISBN 978-1-77108-630-1 (softcover).--ISBN 978-1-77108-631-8 (HTML)

I. Hodd, Thomas Patrick, 1972-, editor II. Title.

PS8503.I67A6 2018 C813’.52 C2018-902858-0

C2018-902859-9

Nimbus Publishing acknowledges the financial support for its publishing activities from the Government of Canada, the Canada Council for the Arts, and from the Province of Nova Scotia. We are pleased to work in partnership with the Province of Nova Scotia to develop and promote our creative industries for the benefit of all Nova Scotians.

To Master Warrant Officer Daniel Joseph Hodd, and to all the soldiers who struggle to tell their stories

Introduction

Trench-fighter, military medallist, and the “unofficial Bard of the Canadian Expeditionary Force,” according to historian Jonathan Vance, Will R. Bird (1891–1984) dedicated much of his life to storytelling. Over a writing career that spanned more than five decades, the Nova Scotia-born author amassed a store of travel pieces, short stories, novels, edited books, and other works of non-fiction that number in the hundreds. He published more than a dozen novels, as well as a history of Nova Scotia. He also wrote two memoirs, a handful of poems, and several dramatic pieces. But what many Canadians don’t know is that a large portion of these publications were inspired by Bird’s experience as a combat soldier during the First World War. What’s more, had it not been for a belief in the supernatural he might never have seen action at all, let alone wrote about it.

Born in East Mapleton, near Amherst, Nova Scotia, Bird’s early years were marred by emotional and financial hardship: his father died when Bird was four years old; he was also forced to leave school in grade eight to help support his family, before moving out west a few years later. To make matters worse, while his friends and even his youngest brother, Stephen, had been able to join the war effort, Bird had been rejected twice due to medical reasons. Then, in 1915, while working in a field in Saskatchewan he saw an apparition of his brother:

I was […] pitching sheaves on a wagon, when Steve walked around the cart and confronted me. He said not a word but I knew all as if he had spoken, for he had on his equipment and was carrying his rifle. I let the fork fall to the ground and the nearest man came running to me, thinking I had taken ill. I did not tell him what I had seen, but I left the field, and never pitched another sheaf of grain. All that day, and the next, and the next, I wandered by myself around the prairie, and then the message came, a wire, ‘Steve has been killed. Come home.’” (And We Go On, 8–9.)

Bird returned to Nova Scotia and tried again to enlist. This time he was successful, and was assigned to the 193rd Battalion, the Nova Scotia Highlanders, although he was eventually transferred to the 42nd Battalion to serve out the remainder of the war with the Black Watch. He first saw action in the fall of 1916, and spent a short time as a sniper before turning patrolman. He also took part in some of the most important battles of the First World War, fighting at Passchendaele and Amiens, as well as at Arras and Cambrai. Remarkably, he survived the war with no lasting physical injuries, an impressive feat for an infantryman. He was even awarded a Military Medal for Bravery at Mons, Belgium, on the final day of the war.

After being demobilized, Bird moved back to Nova Scotia and, for a brief time, ran a general store before having to close shop and take a job at the local post office. Then in the early 1920s, he entered his first writing contest and won, which inspired him to begin sending out his stories for publication. Success soon followed. He decided to try his hand at writing full time, but in order to do so he needed to find a subject that would interest readers. Luckily for Bird, very few veterans wanted to write down—or even talk about—their experiences in the trenches, so he made it his mission to tell their stories.

The result? No Canadian author who served overseas has published more on the First World War than Will R. Bird. Although a handful of his contemporaries, such as Prince Edward Island native Basil King and Ontario writer Ralph Connor, each published maybe a handful of novels on the subject, during the early 1930s the Great War became almost an obsession for Bird: he penned no fewer than five books on the subject as well as numerous short stories and other non-fiction pieces. His main non-fiction works include Thirteen Years After: The Story of the Old Front Revisited (1932) and The Communication Trench (1933). He also wrote a novel, Private Timothy Fergus Clancy (1930). His most lasting book from this period, however, is his soldier memoir, And We Go On (1930), recently republished with McGill-Queen’s University Press. It has become a staple for Canadian military historians and to those interested in reading about the soldier experience during the First World War.

But a memoir about the soldier experience does not capture the imagination in the same way that a novel or short story might. Equally curious, the majority of Canadian fictional responses to the First World War published during and after the conflict tended to be novels, not short stories. So once again Bird chose the road less travelled: beginning in the late 1920s and continuing for the next two decades, he published more than fifty war stories. His tales of courage, survival, and self-doubt eventually appeared in a variety of publications and trade magazines, including Maclean’s, Colliers, the Toronto Star Weekly, and the Maritime Advocate and Busy East. Most of Bird’s war stories, however, first found a home in one of three literary outlets: the Legionary, a magazine launched in May 1926 and meant almost exclusively for military veterans; the short-lived New York “pulp” magazine War Stories; and the Canadian pulp periodical, Canadian War Stories, published out of Chatham, Ontario, but which lasted less than a year. The majority of these publications are no longer in print, nor are they digitized. So for the last several decades Will Bird’s extraordinary tales of war have fallen ever deeper into Canadian literary obscurity.

Until now.

This selected edition of Will Bird’s war stories represents less than a third of his combat tales. In making the selections I have tried not only to choose the best stories in terms of detail and depth, but also to demonstrate how diverse they were in terms of perspective and outcome. For instance, although Bird served with the Nova Scotia Highlanders and the Black Watch, he did not limit his stories to personal battalion experience. The tale “White Collars,” for example, is about the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry, while “Sunrise for Peter” is about the Newfoundlanders. Nor did Bird confine himself to stories about Canadian soldiers: the last piece in this collection, “A Soldier’s Place,” is about an American veteran, whereas Australians take centre stage in “The Creeping Phantom.” Even more extraordinary are those moments when Bird pushes his imaginative powers to new heights, as when he describes the emotiona

l roller coaster of a young woman named Priscilla who goes searching for the soldier she fell in love with at Union Station in Toronto, or when he reveals the inner fears of a Canadian flying ace in the RAF, or when he articulates the despair of a German soldier named Otto in “The Russian Coat.”

In addition to the stories is a short bibliography as well as a selected glossary to help readers with military terms, references, and slang sayings common during the First World War period. I hope that after reading these tales you will have a better appreciation for Bird’s craft as a short-story writer, and for his ability to capture the emotional trials of the soldier experience, the horrors of trench warfare, and the camaraderie that can emerge in times of war. This collection may also go some way to help kindle (or rekindle) your interest in Will Bird’s other writings, which have likewise fallen into obscurity. Above all, it must be said that this book is more than a recovery project: it is a celebration of one of Canada’s great writers, who was both a combat veteran and a proud Maritimer.

His Deputy

It was an inky black night at Aldershot Camp, one of those soft, suffocating kinds of night that make a person unaccountably irritable. Private “Red” McLean of the Second Battalion, Nova Scotia Highlanders, was coming into camp by way of the brigade road, trusting to find his way by the feel of the ground under his heavy army boots. A glimmer of light to his left told the location of the brigade guard tent. It was an hour after Last Post had blown, but Red was noted for his indifference to army regulations. He neither swerved towards the guard tent to report nor stole cat-footed by way of the rear, but bumped solidly into a sentry who stood leaning on his rifle.

“Halt; who goes there?” It was the recruit’s first turn on guard and he was excited.

“If you p-punch me again with that f-fool bayonet I’ll knock you b-back to the barnyard,” came Red’s answer. “Q-quit your yellin’. I’m McLean of B Company, Second Battalion.”

“Where’s your pass?”

“In my p-pocket. Why?”

“You come to the light and show it,” ordered the sentry.

There had been a mild commotion in the guard tent and a sergeant came outside holding a flickering candle.

“Y-you first battalion guys are n-nuts on this guard stuff,” growled Red, but he followed the sentry.

There came a shouted command. Two individuals, one bearing a flashlight, had appeared and the guard turned out with the awkward haste of new soldiers. The officer of the night was making his “rounds.”

Red shuffled by his attendant, who had halted in a bewildered manner, and unfolded his pass in the candlelight. “Here’s your p-pass,” he called roughly. “C-come and have a p-peek at it.”

The officer ordered the guard to “stand at ease,” and, accompanied by his sergeant, went to the tent.

“Who are you and what are you doing here?” he demanded of Red.

Red let his eyes travel over the lieutenant, from the polished brown boots to trim balmoral. Identical in build, with the same cut of chin and broad independent nose, blue eyes and red hair—here was his twin if ever there were twins!

“This g-guy wanted to see my p-pass.” He indicated the perspiring sentry.

“I asked who you were.” There was nothing sarcastic in the remark, only mild insistence. “No. 8778 P-private Murdock Malcolm M-McLean, B Company, Second Battalion.”

“What platoon?”

“S-six.”

“Say ‘sir’ when you’re speakin’ to an officer,” snapped the sergeant.

“Six, s-sir.”

The “sir” was drawled with just a touch of insolence and the NCO’s eyes gleamed angrily.

The officer scanned Red curiously.

“Ye gods!” he murmured, as if to himself. Then he smiled. “Some coincidence,” he remarked. “My name is Murdock Malcolm McLean, and today I’ve been given command of number six platoon. Are you from Cape Breton?”

“No,” said Red shortly, then added, “Sir-r.”

The lieutenant’s smile faded. “Carry on,” he said to the sergeant, and left the tent. Red lurched out into the dark and disappeared.

On his blankets in a tent noisy with varied snoring Red twisted about in a vain effort to sleep. Every time he shut his eyes he could see that replica of himself in carefully tailored tunic and glistening Sam Browne; could hear that soft, cultured voice say, “Ye gods!”

“Some blankety-blank three weeks’ wonder p-playin’ at soldierin’,” he swore to himself a dozen times.

The next morning the wag of six platoon bowed gravely to Red and stuck out his hand. “Never knew your twin was in the army,” he said gravely. “When do you get stripes?”

“W-what do you mean?” asked Red in ominous tones.

“If that new ‘looey’ isn’t your brother, Nature’s done a lot for nothin’,” came the reply amid shouts of laughter. “You must be his deputy, anyhow.”

Red’s reply was drowned in the raillery that followed, but his fist caught the wag on the chin and that gentleman went down heavily.

“Any more want to have fun?”

No one replied. They were astounded by Red’s fury, and helping the wag to his feet, they filed down to the mess tables murmuring among themselves.

Red had signed up in ’14, but after a hectic week at Valcartier with the First Contingent, had been discharged on account of a missing third finger on his left hand. Fierce arguments had availed him nothing. Men were aplenty, and over plenty, and so he went back to the logging camps with a grouch that did not leave him. Early in ’16 he learned that men were needed badly for the Highland Brigade of Nova Scotia, and found that two years had made a vast difference in physical requirements. He was passed without a question, and the smouldering fire he nursed was fanned to a flame. If he were fit in ’16, he had been fit in ’14, he complained to all who would listen. Soon he was more or less shunned, not comprehending that many of his listeners had borne the same disappointments, and the appearance of Lieutenant McLean gave him a subject on whom to vent his spleen.

“The dude has dodged the war till the women have run him out of their parlours,” he declared, and found no listeners.

The officer with red hair and blue eyes was popular with his men, from the hour of his arrival.

The Second Battalion was proud of its athletes. There were many sprinters in the ranks, a nifty baseball nine, good wrestlers, and last but not least, promising boxers. Red chose the mitts as his form of recreation, but unfortunately for him, carried into the ring a soured temper that made his boxing not what the instructors desired. Men he met would be roused, and a hammer-and-tongs contest generally resulted.

One evening, as he lingered by the ropes awaiting a suitable opponent, he was amazed to see his platoon officer leap into the ring, arrayed in boxing togs. Without waiting to see whether the officer was to meet another or not, Red hopped the rope barrier and saluted mockingly.

“Any objections to swappin’ a few?” he asked in a strained voice.

“Why, no, McLean. Not the slightest,” said the lieutenant good-humouredly. “Get someone for timer.”

Stripped for action, it was seen that the officer was the lighter of the two by several pounds, and he had not the bulky muscles that Red had acquired in many lumber camps, yet his reach was as long and his greater speed was undeniable. In addition, he was a cool and experienced boxer. Red soon found this out, but his determination to “down” his man over-ruled his better judgment. He tore in like a mad bull, and by chance one of his battering rights rocked the lieutenant. A fierce joy fired Red to greater efforts, but the round ended before he could follow up his advantage. When the second round finished Red felt that he had encountered a boxing octopus. Hard-driven mitts had met him from all directions; he had been jabbed to dizziness; one eye was completely closed, and a vast weariness had seized his knees.

Dimly Red

realized that Lieutenant McLean must be a far harder-boiled gent than he seemed. The private had no idea of quitting, however, though he was forced to clinch desperately throughout the third round. To his surprise he found this easy to do, and did not comprehend its meaning until the timer leaned over and whispered, “That guy let you go the round, but you better pull the mitts off. You’d be pie for him if he wanted to finish it.”

A gory mist blinded Red. “Let me go, did he?” he snarled. “Tell him he’s lyin’. I’ll show you this time!”

He launched an attack more like the onslaught of a wild beast than that of a boxer, but his swinging fists never landed. In turn, padded pile-drivers drove him back relentlessly. In vain he tried to rally, to break down the barrage by sheer strength. His opponent seemed made of spring steel. Bright lights danced across his vision. As he staggered back he released all his reserve in one wild swing. That swing was unexpected by his conqueror, and it landed flush on the “button.” The lieutenant went down like wet paper!

Red was too groggy to appreciate his victory for some time, and then he read enough contempt in the eyes of onlookers to understand that the officer had lost nothing by the bout.

From that evening Red never went in the ring again, but his fires of hate still simmered unceasingly and his prejudiced imagination tried hard to find wrongs aimed his way. He failed in this, however, for Lieutenant McLean joked off their match and was ever just in his rule of the platoon.

The battalion went to England, and there Red welcomed an opportunity to escape the Nova Scotia Highlanders and all they meant to him. He volunteered for a draft to the famous Canadian Black Watch, and was in France for his Christmas dinner of bully and lumps of soggy plum duff. It was muddy wherever he went; he was always hungry, lousy, and was worked long shifts in the trenches, but among his new mates was pronounced a “full” private—meaning that he would take his share of bone labour and dirty weather without squealing. They judged he was anxious to acquit himself in new company, but Red was a changed man, because he had at last reached his goal and was among comrades he did not despise.

A Soldier's Place

A Soldier's Place